Zero hunger

Children in the Santeng community of Tongo District, Ghana, enjoy porridge made from fonio, an ancient indigenous drought-resistant crop cultivated by rural women.

© WFP/Derrick Botchwayand policy solutions are imperative to address entrenched inequalities, transform food systems, invest in sustainable agricultural practices, and reduce and mitigate the impact of conflict and the pandemic on global nutrition and food security.

In the face of a polycrisis, joint global efforts are urgently needed to address hunger and ensure food security

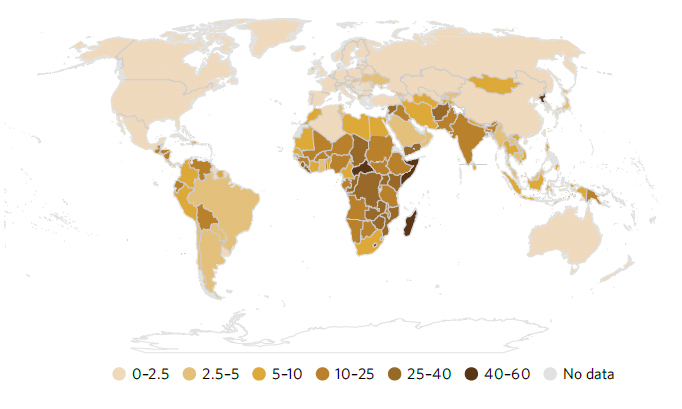

In 2022, the prevalence of undernourishment remained unchanged compared to 2021, following a significant increase in 2020 due to the pandemic and a slower rise in 2021. The global population facing chronic hunger stood at 9.2 per cent in 2022, up from 7.9 per cent in 2019, affecting around 735 million people, which is a rise of 122 million since 2019. Moreover, an estimated 2.4 billion individuals, equivalent to 29.6 per cent of the world’s population, experienced moderate to severe food insecurity, meaning they did not have regular access to adequate food. While Africa has a higher proportion of its population facing hunger compared to other regions, Asia is home to the majority of people facing hunger. It is projected that more than 600 million people worldwide will be facing hunger in 2030, highlighting the immense challenge of achieving the zero hunger target.

Global trends in the prevalence of hunger and food security reflect the interplay of two opposing forces. On one hand, the resumption of economic activity has led to increased incomes and improved access to food. On the other hand, food price inflation has eroded income gains and hindered access to food. However, these forces have manifested differently across different regions. Hunger continues to increase in Western Asia, the Caribbean, and all subregions of Africa. Conversely, most subregions in Asia and Latin America have experienced improvements in food security.

Prevalence of undernourishment, 2020–2022 average (percentage)

Aid and public spending on agriculture are falling despite the growing global food crisis

Investment in agriculture is crucial for improving efficiency, productivity and income growth, and for addressing poverty and hunger. Despite record-high nominal public spending on agriculture of $700 billion in 2021 during the pandemic, government expenditures on agriculture relative to the sector’s contribution to GDP (as measured by the agriculture orientation index – AOI) fell from a value of 0.50 in 2015 to 0.45 in 2021. This decline was observed in all regions except Europe and Northern America, where stimulus packages of unprecedented scale were implemented by governments. Latin America and the Caribbean recorded the highest decline in AOI, from 0.33 in 2015 to 0.21 in 2021.

Between 2015 and 2021, the total aid to agriculture in developing countries increased by 14.6 per cent, from $12.8 to $14.2 billion (in constant 2021 prices). In 2020, total aid to agriculture spiked, growing by nearly 18 per cent compared to the previous year, partly due to food security concerns during the pandemic. However, in 2021, it fell by 15 per cent, returning to levels similar to those before the pandemic.

Malnutrition continues to threaten children and women worldwide, despite some progress

Children affected by malnutrition – including stunting (low height for age), wasting (low weight for height), micronutrient deficiencies, and by being overweight – face heightened risks of poor growth and development. Despite progress in certain regions, child malnutrition remains a global concern that has been exacerbated by the ongoing food and nutrition crisis – with low- and lower-middle-income countries among those most affected.

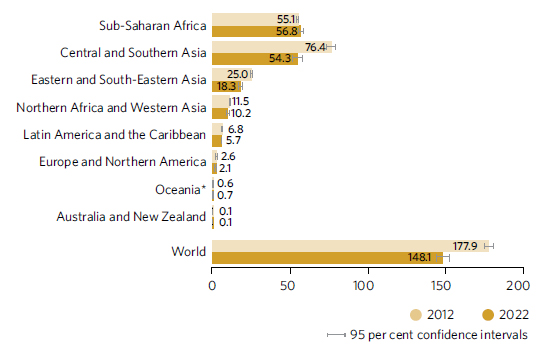

In 2022, 22.3 per cent of children under age 5 (148 million) were affected by stunting, down from 26.3 per cent in 2012. While the number of countries with a high prevalence of stunting (30 per cent or more) decreased from 47 to 28 countries from 2012 to 2022, no region is on track to achieve the 2030 target of a 50 per cent reduction in the number of stunted children. If current trends persist, approximately 128.5 million children will still suffer from stunting in 2030. To meet the global target, the annual rate of reduction must increase by 2.2 times the current rate.

Wasting, caused by diseases and nutrient-poor diets, puts children at immediate risk of thinness, weakened immunity, developmental delays and death. In 2022, 6.8 per cent (or 45 million) children under age 5 were affected by wasting, down form 7.7 per cent in 2010. At the same time, 5.6 per cent (or 37 million) were overweight. The global prevalence of overweight children has stagnated at around 5.5 per cent since 2012, requiring greater efforts to achieve the 2030 target of 3 per cent.

Moreover, the prevalence of anaemia in women aged 15–49 continues to be alarming, stagnating at around 30 per cent since 2000. Anaemia in women is a risk factor for adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes, highlighting the importance of addressing this issue for both women and child health and nutrition.

Preventing all forms of malnutrition requires: ensuring adequate maternal nutrition; promoting optimal breastfeeding; providing nutritious, diverse and safe foods in early childhood; and creating a healthy environment, with access to basic health, water, hygiene and sanitation services, as well as opportunities for safe physical activity. Coordinated actions across nutrition, health and social protection sectors – especially in the regions most affected – are needed to reduce child and maternal malnutrition.

Number of children under age 5 who are affected by stunting, 2012 and 2022 (millions)

Proportion of children under age 5 who are overweight, 2012 and 2022 (percentage)

* Excluding Australia and New Zealand.

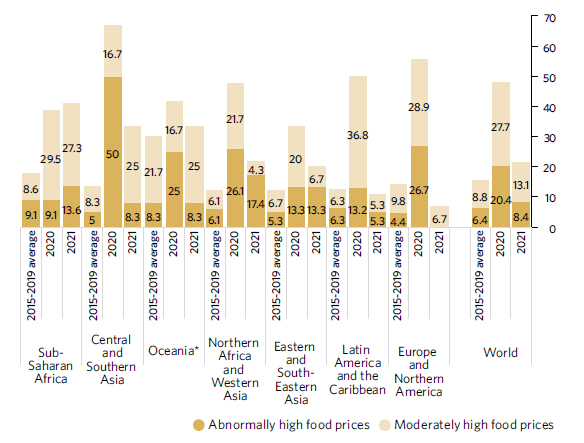

Despite dropping in 2021, the share of countries experiencing high food prices remained above the 2015–2019 average

Globally, the share of countries experiencing moderately to abnormally high food prices fell from 48.1 per cent in 2020 to 21.5 per cent in 2021. Despite this significant drop, the 2021 figure was still higher than the 2015–2019 average of 15.2 per cent. Factors such as increased demand, rising input (energy and fertilizer) and transport costs, supply chain disruptions and trade policy changes contributed to the sustained price increases. Meanwhile, domestic factors – including adverse weather, currency depreciations, political instability and production shortfalls – intensified price pressures. In sub-Saharan Africa and the least developed countries (LDCs), the proportion of countries experiencing high food prices increased for the second consecutive year in 2021 (reaching 40.9 per cent and 34.1 per cent, respectively). These regions faced additional challenges from worsening security conditions, macroeconomic difficulties, and a high level of dependency on imported food and agricultural inputs.

Proportion of countries affected by moderately to abnormally high food prices, 2015–2019 average, 2020 and 2021 (percentage)