Reduced inequalities

Migrants cross the dangerous Darien jungle between Colombia and Panama, which saw a seven-fold increase in the number of children in the first two months of 2023 compared with 2022.

© UNICEFand skills development, implementing social protection measures, combating discrimination, supporting marginalized groups and fostering international cooperation for fair trade and financial systems.

Most countries experienced increased shared prosperity, but the pandemic may have reversed some of this progress

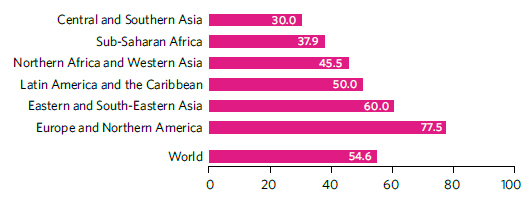

Among countries with data for 2009-2022, more than half achieved income growth for the poorest 40 per cent of the population at a rate higher than the national average. But the share of countries that experienced shared prosperity was higher in high- and middle-income regions than in their fragile and low-income peers. More than three-quarters of countries in Europe and Northern America and 6 out of 10 countries in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia saw the incomes of the poorest 40 per cent grow faster than the national average. However, in Central and Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, the incomes of the poorest 40 per cent grew faster than the mean in only 30-38 per cent of countries.

Post-2019 data are still sparse and inconclusive. In two thirds of the 50 countries with data, the poorest 40 per cent experienced higher income growth than the national average. However, this trend is largely driven by Europe and Northern America where more data are available and where large transfer programmes have mitigated COVID-19's economic impacts on the bottom of the income distribution. Emerging evidence indicates that inequality within countries may have worsened as a result of the pandemic, with surveys in 2021 showing that poorer households lost incomes and jobs at slightly higher rates than richer households.

Share of countries where income growth of the poorest 40 per cent of the population is higher than the national average, 2009-2022 (percentage)

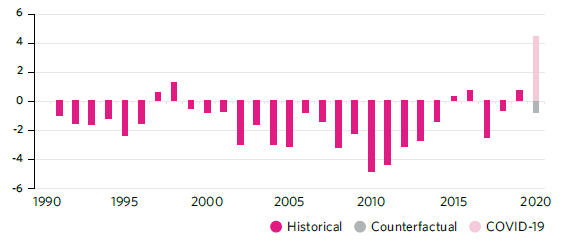

The pandemic has caused the largest rise in income inequality between countries in three decades

Over the past three decades, incomes in lower and middle-income countries have been catching up to those of richer countries. Overall, the income differences between countries decreased by 37 per cent between 1990 and 2019. Recently, however, this convergence has slowed considerably. The average annual decline in inequality between countries in the last five years before the pandemic was 0.3 per cent, much lower than the average annual reduction of 1.8 per cent between 1991 and 2014. And although there had been increases in global between-country inequality in only 5 of the 29 years before the pandemic, the onslaught of COVID-19 has caused the largest increase in between-country inequality in three decades, according to World Bank estimates.1 Between-country inequality is projected to have risen 4.4 per cent between 2019 and 2020, compared with the pre-pandemic forecast of a 0.8 per cent reduction.

Change in inequality between countries, 1990-2020 (percentage)

Note: The annual changes in inequality between countries use the mean log deviation.

Racial discrimination is one of the most common grounds for discrimination worldwide

The latest available data show that close to one in six people globally experience discrimination based on any grounds. Among both women and men, racial discrimination, rooted in factors such as ethnicity, colour or language, is among the most common grounds. Discrimination based on age and religion, though slightly less widespread, also affects women and men almost equally. Women are twice as likely as men to report instances of discrimination based on sex and almost twice as likely as men to experience discrimination on the basis of marital status. Persons with disabilities also encounter high levels of discrimination, with one in three reporting such experiences, twice the rate encountered by individuals without disabilities.

Proportion of the overall population experiencing discrimination, by selected grounds and sex, 2015-2022 (percentage)

With deaths along migratory routes rising globally, urgent action is needed to ensure safe migration

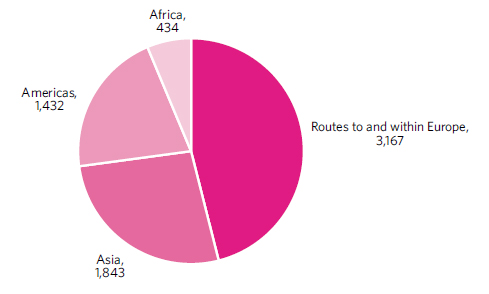

According to the Missing Migrants Project of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), a total of 56,216 deaths on migratory routes worldwide have been recorded since 2014, of which 6,876 were in 2022 and 2,091 were as of mid-June 2023. With the exception of 2020, more than 5,000 deaths hadbeen documented during migration each year between 2014 and 2022.

In 2022, at least 3,167 people died on maritime and land routes to and through Europe, accounting for more than half of the fatalities recorded worldwide that year. It was also the deadliest year in the Americas and Asia since data collection began, with 1,432 and 1,843 individuals losing their lives during migration, respectively. These data show lack of progress in reducing migrant deaths worldwide since 2015. While there was a decline in deaths during the first year of the pandemic, the numbers have since returned to pre-pandemic levels and in many cases even surpassed them.

Number of deaths during migration, by region, 2022

Note: The regions correspond to IOM regional definitions.

Record numbers of people are fleeing their countries in the face of mounting crises

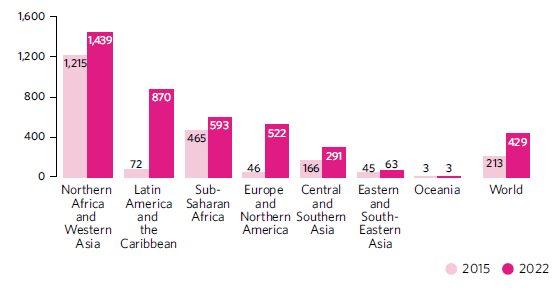

The global number of refugees has increased annually for more than a decade, reaching 34.6 million by the end of 2022, the highest number ever recorded. This represents 429 out of 100,000 people, or 1 in 233, who fled their countries of origin owing to war, conflict, persecution, human rights violations or events seriously disturbing the public order. This represents an increase of more than 100 per cent compared with 2015. Overall, 52 per cent of all refugees and other people in need of international protection came from just three countries: the Syrian Arab Republic (6.5 million), Ukraine (5.7 million) and Afghanistan (5.7 million). Around 41 per cent of all refugees at the end of 2022 were children, while 51 per cent of refugees were women and girls. Low- and middle-income countries hosted 76 per cent of the world's refugees and other people in need of international protection, with the LDCs providing asylum to 20 per cent of the total.

Proportion of the population who are refugees, by region of origin, 2015 and 2022 (per 100,000 population in the region of origin)