Life on land

Villagers in China’s eastern Yunhe County revive hillside farms with eco-friendly practices, attracting global visitors and earning recognition as a top ecotourism destination for the restoration of its ecosystem.

© UNEP/Braunosarus StudiosDeforestation and forest degradation remain major global threats

Forests are among the largest carbon and biodiversity reservoirs on Earth, crucial for mitigating climate change and providing essential goods, services and livelihoods. However, nearly 100 million hectares of net forest area have been lost over the past two decades. Global forest coverage decreased from 31.9 per cent in 2000 (4.2 billion hectares) to 31.2 per cent (4.1 billion hectares) in 2020. Agricultural expansion is the direct driver of almost 90 per cent of global deforestation (cropland accounts for 49.6 per cent and livestock grazing for 38.5 per cent). Oil palm harvesting alone accounted for 7 per cent of global deforestation from 2000 to 2018.

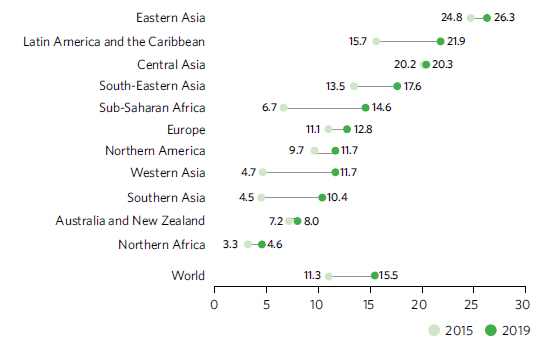

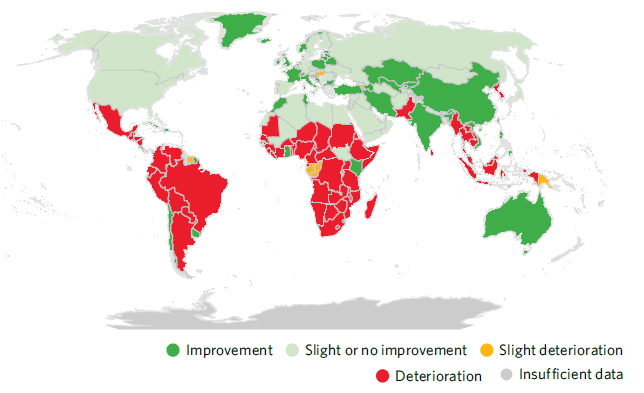

Agriculture consumed large forested areas in many countries across Latin America, the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia between 2015 and 2020. Conversely, many countries in Asia, Europe and Northern America maintained or increased their forest area over the same period. Global and regional efforts to sustain forest ecosystems as well as their social, economic and environmental functions are essential, in particular for developing countries and the tropics.

Trend in forest area as a proportion of total land area, 2015–2020

Note: Trend categories are based on thresholds for the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) between 2015 and 2020 as follows: Improvement: CAGR > 0.001; Slight or no improvement: -0.0005 ≤ CAGR ≤ 0.001; Slight deterioration: -0.001 ≤ CAGR < -0.0005; Deterioration: CAGR < -0.001.

Despite efforts to mobilize financing for biodiversity conservation, a persistent funding gap remains

Halting and reversing biodiversity loss requires a comprehensive approach combining regulatory and voluntary measures, while mobilizing and aligning financing for biodiversity. Economic instruments play a crucial role in incentivizing the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity – and can serve to mobilize finance and mainstream biodiversity across sectors. They include policy instruments such as biodiversity-related taxes, fees and charges, positive subsidies, payments for ecosystem services and biodiversity offsets. ODA is another source of financing for biodiversity.

Between 2017 and 2019, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reported that 234 biodiversity-related taxes in 62 countries generated $8.9 billion annually and payments for environmental services in 10 countries mobilized $10.1 billion per year. In 2021, ODA in support of biodiversity increased by 26.2 per cent from $7.7 billion (constant 2021 prices) in 2020 to $9.8 billion. This rise can be attributed to international commitments such as the Aichi target on development finance, the recognition of the links between infectious diseases and ecosystem destruction in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the parallel focus on addressing climate change and biodiversity loss. But despite progress, there remains a persistent funding gap for biodiversity conservation, emphasizing the need to scale up the use and ambition of economic instruments to protect biodiversity.

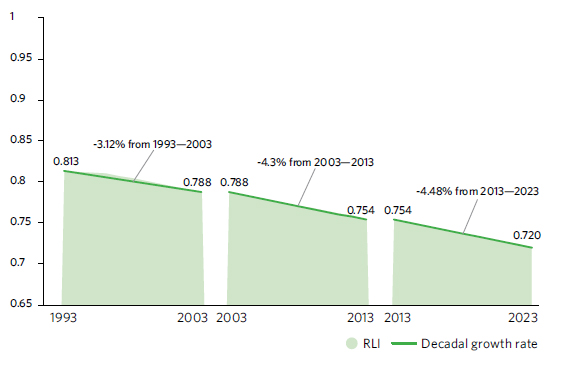

Species extinction risk has accelerated each decade since 1993

Plant and animal species are vital for our existence, from pollinating one third of global crops to providing medicines and economic opportunities. Yet, despite this importance, the world is currently facing the largest extinction event since the dinosaurs disappeared. Habitat destruction, invasive species, overexploitation, illegal wildlife trade, pollution and climate change are propelling this crisis. The Red List Index, which measures species’ extinction risk across mammal, bird, amphibian, coral and cycad species, has deteriorated by about 11 per cent since 1993, with an accelerating decline each decade. Central and Southern Asia, Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, and Oceania have suffered the fastest declines.

In 2022, assessments revealed that 21 per cent of reptile species are threatened, including the iconic Komodo Dragon in Indonesia, highly valued for ecotourism but endangered by climate change and deforestation. Based on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, it is estimated that 1 million species globally may be threatened with extinction. Urgent action is imperative to halt these potential losses, as they would have irreversible and profound impacts on nature and pose a serious threat to human well-being.

Red List Index rate of decline, by decade, 1993–2023 (Red List index and growth rate)

Growth in protected area coverage of key biodiversity areas has largely stalled

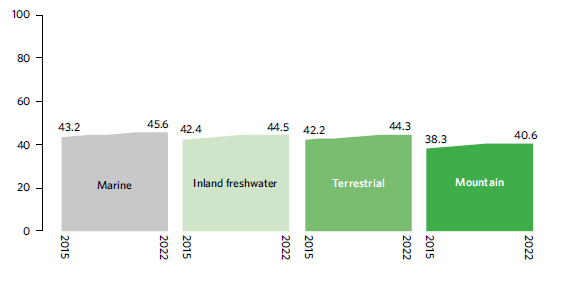

Key biodiversity areas (KBAs) – areas of exceptional importance for species and ecosystems – are crucial for conservation and sustainable development. There are more than 16,000 KBAs globally, and since 2000, the average coverage of KBAs by protected areas has nearly doubled across marine, terrestrial, freshwater and mountain ecosystems. However, progress has largely stagnated since 2015, with uneven growth across regions. The Europe and Northern America region has more than half of its KBAs covered by protected areas, while Central Asia, Southern Asia, Western Asia, Northern Africa, and Oceania all have relatively low coverage. The recently adopted Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework represents a new political commitment providing impetus to increase the protected area coverage of KBAs to help safeguard the most significant natural habitats on our planet.

Mean proportion of marine, inland freshwater, terrestrial and mountain KBAs covered by protected areas, 2015–2023 (percentage)

Alarming trends in land degradation call for urgent action to restore the Earth

Between 2015 and 2019, at least 100 million hectares of healthy and productive land were degraded every year, affecting food and water security globally. The loss is equivalent to twice the size of Greenland, impacting the lives of 1.3 billion people, who are estimated to be directly exposed to land degradation. Human activities like urban expansion, deforestation and grassland conversion, coupled with climate change are direct drivers of land degradation worldwide. Demographic and economic trends, governance challenges, and technology and investment gaps also contribute indirectly.

Sub-Saharan Africa, Western Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Southern Asia experienced land degradation at rates faster than the global average. If current trends continue, restoring 1.5 billion hectares of land by 2030 will be necessary to achieve a land-degradation-neutral world. Alternatively, halting any new land degradation and accelerating existing commitments to restore 1 billion hectares can surpass the neutrality target. Land and ecosystem restoration offer cost-effective solutions to address climate change, biodiversity loss, food and water security, and disaster impacts. To this end, governments, businesses and communities must collaborate to conserve natural areas, scale up nature-positive food production and develop green urban areas, infrastructure and supply chains.

Proportion of degraded land, 2015 and 2019 (percentage)